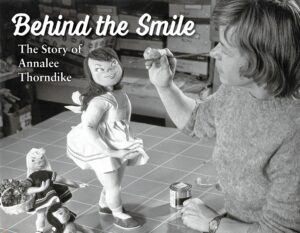

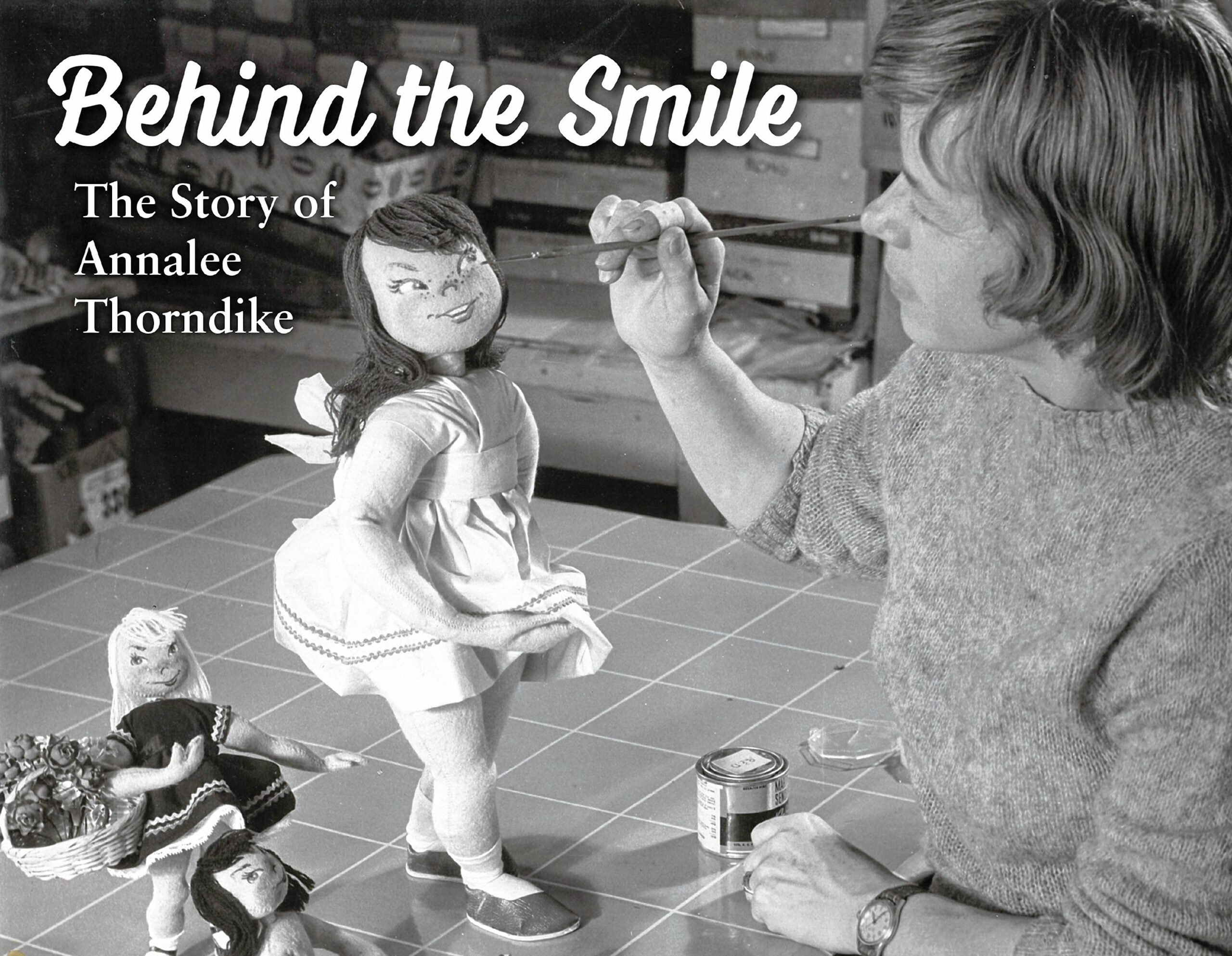

Behind the Smile: The Story of Annalee Thorndike is the first-ever illustrated biography of the legendary doll maker. Her story is a tale of self-sufficiency, live-free-or-die resiliency, and a life-long passion to create. Her dolls would define her life, and many say that each of her dolls is in some way a reflection of the woman herself and her playful personality.

Behind the Smile: The Story of Annalee Thorndike is the first-ever illustrated biography of the legendary doll maker. Her story is a tale of self-sufficiency, live-free-or-die resiliency, and a life-long passion to create. Her dolls would define her life, and many say that each of her dolls is in some way a reflection of the woman herself and her playful personality.

Annalee Thorndike began making dolls as a child in Concord in the 1920s. Her passion to create was inspired by her artist mother and the many creative people she associated with, but at its core was her vivid imagination. She was blessed with dexterous fingers, a love of design and color, and a quicksilver temperament and curiosity. She was only four or five when she began playing with fabrics, lace, colored pencils, and paper to design dolls. Her dreams of making dolls would lead to a life-long career.

The dolls she created are recognized as among the most collected and loved dolls everywhere. She would also, along with her husband Chip, build a successful company that would become both a tourist destination as well as one of the largest employers in New Hampshire. Today that company continues to share her legacy with new generations of doll collectors.

Annalee dolls are known for their felt fabric, whimsical and mischievous faces, and creative positioning. Made for collectors and decorating around the home, Annalee fashioned her dolls from everyday life and the simpler times she knew in rural New Hampshire. They also reflect her wicked sense of humor. Her early dolls were about occupations, sports, and hobbies and then expanded to include her now-famous mice and elves. These little critters became a staple in the holiday and seasonal decorations for millions of people.

Behind the Smile: The Story of Annalee Thorndike is available at the Annalee Gift Shop, 339 Daniel Webster Highway, Meredith, or online at Annalee.com.

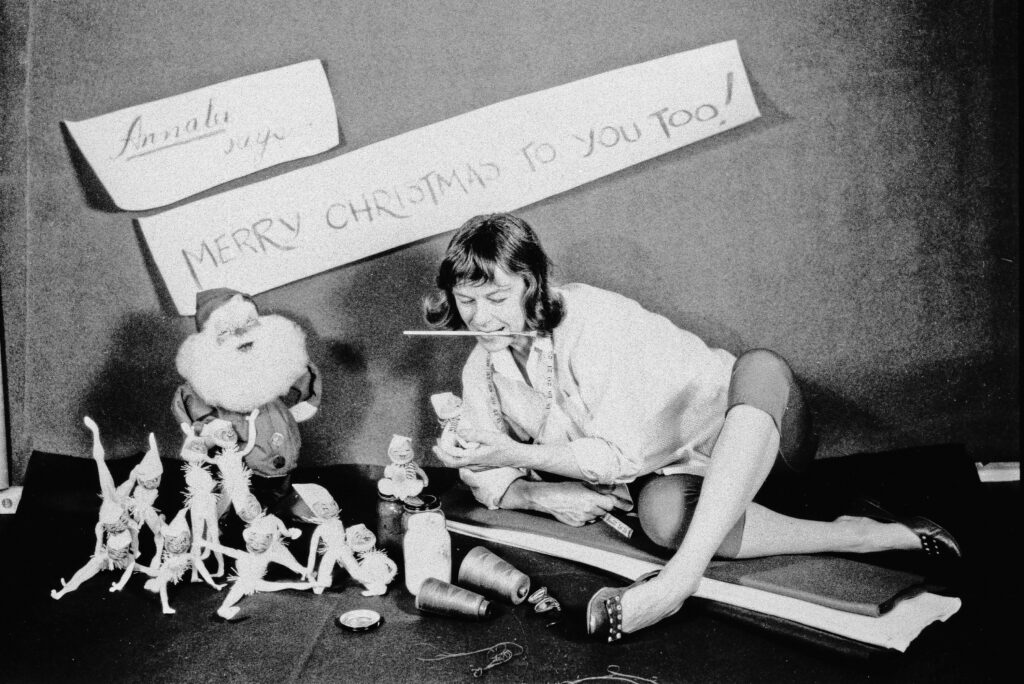

Whimsical elves and Santas have been a cornerstone of Annalee Thorndike’s doll designs for almost a century. Annalee would hand paint all the faces on her dolls.

The Bottom Drops Out

Where once there were 32,000 Rhode Island Red chickens roaming around the Thorndike farm, the number eventually dwindled to a much, much smaller amount. In the early 1950s, the bottom fell out of the poultry business. Chip and Annalee Thorndike could no longer make a decent living selling hatchlings and eggs. Faced with mounting debt, they began looking for new ways to make a living. The couple would sell the additional farm they had purchased, keeping only their primary residence at Reservoir Road. Chip would take a part-time job at a knitting machine manufacturing company in Laconia while also tending to his remaining chickens and auto supply store.

It was not a happy, or warm, time for the Thorndikes. With no bank willing to lend them the money to finish some major home repairs, the family used a canvas tarp to cover an unfinished wall of the house during the winter months. It was out of this cold that the seeds of new business would sprout. Out of necessity, Annalee would return full-time to doll-making.

Starting in her childhood bedroom in Concord, Annalee Thorndike began designing artistic doll masterpieces made out of felt. She honed those skills throughout her life. Eventually, her family, including her husband Chip and sons Chuck and Town, would help make her designs known worldwide.

That humble piece of furniture, the kitchen table, has served as the incubus for many a business. Certainly it did for Annalee Dolls. It was at the sunlit kitchen table in the Thorndike’s farmhouse where Annalee would begin her business in earnest. The operation expanded to the larger dining room table, then the living room, and then the upstairs, until dolls spilled out of every corner of the house. Annalee would make the dolls and Chip would find ways to sell them, delivering orders in the family Volkswagen. Annalee remembered: “It was quite a sight to see Chip barreling down the highway with a carload of dolls.” She also remembered having to clear off her materials from Chuck’s and Town’s beds before they could go to sleep at night. The house was full of dolls and doll parts.

It was Chip who would make another major contribution to the dolls. Annalee firmly believed her dolls should always be in a permanent position. To do this she had to find ways, sometimes extremely difficult, to sew them into those positions. Chip devised the internal metal frame that is still used in the dolls so that each doll could stay in place, just as his wife envisioned them.

Word of the petite dollmaker’s skill, and that of her enchanting dolls, slowly began to spread. It became necessary to hire a group of Meredith women to help in the production of the dolls. Both as homemakers and as friends who gathered around Annalee’s tables, the women filled the expanding order list. Annalee continued to design and make faces for new dolls and expected her assistants to pass rigorous production standards. She established an inspection process to make sure all dolls were made to her high expectations. Work was informal — a coffee klatch atmosphere — yet even in those early days Annalee established clear work procedures. She knew the most economical way to utilize fabric and worked and reworked her designs. She became a perfectionist where her dolls were concerned. And if the truth be known, she sometimes became so attached to a particular doll that she was reluctant to pronounce it “finished” and release it.

There were discouragements and disagreements, as there usually are in a small business — especially one going from a hobby into a full-fledged operation. Chip continued creating new accessories for the dolls, and developed ways to market them, often on a door-to-door basis. The Thorndikes made presents of many of their early dolls to businesses in the Lakes Region of New Hampshire, which displayed them on counters and in store windows, thus heightening their visibility. Friendships were established in those early years that Annalee and Chip would forever treasure.

Success and recognition came very slowly to the fledgling doll company. The company, thus the Thorndike family, struggled to make ends meet in those early years. But little by little, doll by doll, and with lots of persistence, Annalee dolls were finding their way in the marketplace.

Christmas-themed Annalee dolls line the gift store in Meredith.

Annalee focused on expanding her designs and collection of faces. She was continually experimenting with how to paint faces on felt, and stretching the felt, to make sure the faces and every expression looked just right. She also agonized over the positioning of her dolls. Chip’s wireframes gave Annalee more flexibility with her creations, but finding the right “position” for each doll became a painstaking process. If any company could be called family-oriented, this was certainly the case with making the early Annalee dolls. Sons Chuck and Town even joined the family business as mere kids to help tie the shoelaces and fit their mother’s ski boots and shoe gear to the many of the dolls’ feet. In 1955, Annalee and Chip incorporated the company as Annalee Mobilitee Dolls. The creative name perfectly referenced the type of doll as well as Annalee’s and Chip’s contributions to their design and construction.

The company’s dolls had their earliest success as promotional decorations and displays. Many department and specialty stores started featuring the dolls in their windows and sales displays. Jordan Marsh, then the largest department store in Boston, regularly featured the dolls. Annalee also returned to one of her earliest benefactors, the League of New Hampshire Craftsmen, which resold dolls for many years. Chip and Annalee often sought out partnerships with other companies to market the dolls, but most of the marketing was done directly one-on-one with various retailers from the Thorndike home. Through rough-and-tumble determination, by 1960, Annalee dolls were being sold in stores in 40 states in the United States, Puerto Rico, and Canada. The chicken farmers had become successful doll makers.

All About the Face

One of the most unique characteristics of an Annalee doll is its face. Impish features make the dolls immediately recognizable as “Annalee.” What is even more fascinating, though, is the company’s long tradition of creating not one, but many expressions for the doll put into the product line. This was Annalee’s clever way of making the dolls appear to be interacting with one another. She would set up elaborate scenes with multiple characters such as swimmers at a beach and skiers making their way down the mountain. She wanted people to see an expression and be reminded of certain people in their lives.

A range of one to 26 faces are used on any given doll. Certain items, because of the subject they represent or the activity they are engaged in, are limited to one expression. Armed with this knowledge, the savvy collector may seek out the multi-expressions as a way to further enhance the enjoyment of a particular doll. As Annalee put it, “there are expressions to fit almost any position you want to put them in.”

Those whimsical faces we’ve all come to know and love all started with Annalee herself. She painted her earliest faces to resemble her own cheery expression. (Some would say that all the faces are just the various moods of Annalee.) Annalee looked in a mirror to draw her own smiles, smirks, and grins. She would do this over and over again. She detailed each wrinkle, dimple, and squiggly brow hair in the mischievous expressions she made. The artwork was then fine-tuned and tweaked to create each mouse, elf, and animal face that was desired: freckles, whiskers, and a sparkle in the eye were added.

Those whimsical faces we’ve all come to know and love all started with Annalee herself. She painted her earliest faces to resemble her own cheery expression. (Some would say that all the faces are just the various moods of Annalee.) Annalee looked in a mirror to draw her own smiles, smirks, and grins. She would do this over and over again. She detailed each wrinkle, dimple, and squiggly brow hair in the mischievous expressions she made. The artwork was then fine-tuned and tweaked to create each mouse, elf, and animal face that was desired: freckles, whiskers, and a sparkle in the eye were added.

Annalee also looked beyond her own expressions to add more variety to her doll faces. She sought inspiration from her own children, Chuck and Town, as well as the people she worked with. She was an ardent student of people — their movements, their positions, their faces.

According to Gracie Blackey, who worked directly with Annalee for 10 years and currently serves as chief designer at Annalee Dolls, “Annalee studied herself in the mirror. She would go into the ladies’ room and draw herself in the mirror. Once I even goaded her into photocopying her face. She studied proportions, shapes, how the eyes looked, how the mouth looked. She looked at babies’ heads to watch how they grow and change. This helped develop the proportions for our dolls and their frameworks. She had a really good idea of what a face looked like. What was in the here and now.”

Annalee would eagerly devour magazines, newspapers, and greeting cards, studying the facial expression of the people in the photographs and drawings. She also was inspired by the artists of her time, such as Norman Rockwell, Dr. Seuss, Tasha Tudor, Trina Schart Hyman, and many more.

A little-known fact about Annalee is that she greatly admired and was inspired by the unique and exaggerated illustrations featured in Mad magazine, including the satirical cartoon character of Alfred E. Neuman, the boy with misaligned eyes and a gap-toothed smile. Annalee had piles of the magazine saved in her original design studio. When the studio was badly damaged by fire, one of Annalee’s first concerns was to see if her copies of Mad had been destroyed. Luckily for Annalee, one of the company’s employees had saved her magazines.

In the beginning, Annalee painstakingly painted her faces directly onto the felt used for each doll. After her dolls started becoming popular, a more efficient technique was needed to place faces on the dolls. With orders pouring into the Factory in the Woods, it became impossible for Annalee to hand paint each doll. Annalee and Chip turned to the silk-screen method and began printing the faces onto the felt in order to keep up with the demand for the dolls. All of the artwork used for each doll’s face or other markings, like dots on a dog or stripes on a zebra or any of her trademark smiles, is Annalee’s original hand-drawn work.

“The faces we use today are what Annalee actually approved,” Gracie Blackey said. “We can adapt them to give us something new. But they are all Annalee. There are actually millions of ways to present the faces due to her designs.” Whatever the expression, there’s something special and undeniably clever and whimsical in all of Annalee’s face designs. Most importantly, as Annalee always said, “If you smile someone else has got to smile back.” There’s magic in the smile of each and every one of the Annalee dolls.

“Behind the Smile: The Story of Annalee Thorndike” was produced by FirstTracks Marketing. Lou Waryncia is editor; Jessica Lynch Falkenham is director of marketing; Robert Dukette is creative director and designer. Many of the stories were researched and written by Rosemary H. Turner in the 1980s and ’90s. Additional acknowledgments to Chuck and Karen Thorndike, Gracie Blackey, Sue Coffee and Bryan Horton.

View Print Edition

View Print Edition