POLISHING THE OLD GIRL FOR HER 200TH BIRTHDAY IN 2019

During the summer of 2016, the State House dome was surrounded by scaffolding, right up to the eagle. Though people sort of knew what was going on up there, it was still something of a mystery. You could see the scaffolds, you could hear the sounds of hammers and saws, but all of it was too far away, too hidden to get a good look. Word was they were regilding the dome.

During the summer of 2016, the State House dome was surrounded by scaffolding, right up to the eagle. Though people sort of knew what was going on up there, it was still something of a mystery. You could see the scaffolds, you could hear the sounds of hammers and saws, but all of it was too far away, too hidden to get a good look. Word was they were regilding the dome.

In fact, it was perhaps the most extensive restoration of the dome since it was built in 1866. And my job was to take camera in hand and document what was happening up there. No question, it was one of those rare opportunities that was more a privilege than work.

Two years have passed since the work was done, and today the dome shines like new. Just to refresh, you might remember that a few years ago, as the State House neared its bicentennial, it was looking tired. Most obvious was the gold dome littered with black splotches that, from a distance, looked like mold.

At street level the State House was not looking good. Up close it looked even worse. I remember my first time standing next to the dome’s base and seeing the extent of deterioration—the paint flaking off, the wood so rotted you could stick a screwdriver into it, the gold that had turned black. An old building looking old.

At street level the State House was not looking good. Up close it looked even worse. I remember my first time standing next to the dome’s base and seeing the extent of deterioration—the paint flaking off, the wood so rotted you could stick a screwdriver into it, the gold that had turned black. An old building looking old.

UP TO THE DOME

Some may remember that years ago, if you asked nicely, a tour guide might take you up into the State House dome. But that stopped back in the 1980s when the State House roof became off limits and the dome became off limits along with it. The reason for the change isn’t clear, unless you’ve been up there.

New Hampshire’s State House dome is not easy to access. The route begins at a door on the third floor of the State House. From there a staircase takes you up a flight and a half of steps to another door that opens out onto the roof. During the restoration, everything outside that door was in the construction zone. Hard hats were required for anyone venturing onto the roof.

From the door, you follow a wooden walkway across the roof that leads to a stair/ladder over a three-foot-high wall that marks where the 1909 addition meets the original State House. The wooden walk continues to another door, which gets you into the base of the dome itself. There, a narrow circular stair takes you up to the large windowed room at the base of the dome structure. The stairs continue up to the very top lantern.

A few feet east of the dome—on the roof—is where the stairs for the scaffolding started. To go up the scaffold, hard hats weren’t enough. You also needed to strap into a safety harness. There were 12 levels of scaffolding. The first 10 you accessed by stairs. Each step clanged as your boot fell upon it, bang, bang, bang, up, up, up. Your steps seemed to ring out and echo back from the State House Annex across Capitol Street.

Each level had a scaffold floor that circled out and around the dome from which the workers could ply their various crafts and trades. As the dome narrowed near its top, the floor for each level tapered in with it. The stairs ended at the base of the top lantern.

Each level had a scaffold floor that circled out and around the dome from which the workers could ply their various crafts and trades. As the dome narrowed near its top, the floor for each level tapered in with it. The stairs ended at the base of the top lantern.

Though not a skyscraper by any means, being up there had a precarious feel to it that gave one a sense of what it must’ve been like for the original builders and crafters back in 1866. I don’t imagine they had strong, metal scaffolding and a harness system to save them from a fall.

FACE TO FACE WITH THE EAGLE

The last two levels of the dome you got to by climbing an attached ladder, straight up about 20 feet. To make the final ascent more interesting, the ladder, though solidly anchored, rocked slightly from side to side as you climbed. When you got to the upper rung of the ladder you emerged out onto the very top level of the scaffolding—sky above, Concord laid out down below, and the eagle perched right there in front of you.

Yes, you were very exposed, protected from a fall only by the railing that wrapped around the platform work space or the connection of your harness if you hooked onto that rail. If heights make you nervous, this was not a place to hang out for the day.

The eagle dominated the space. Tall and still, it was a bit intimidating. You could reach out and touch him as easily as scratching your face. Details like feathers and the pupils of his eyes, the texture of his legs, and the grip of his talons on the ball where he stood all gave him greater presence. They were things you could never have seen or noticed before, even though you’d seen the eagle every time you came to downtown Concord.

There was something sacred about the space, not just at the top but throughout the entire scaffold structure. It called for reverence, respect. First, there was the potential for falling or tripping. Caution was always on high. But there was something more, something almost spiritual.

It was a space that would only exist for a couple months and be gone just as quickly as it was created. It was a platform in the air, like a magic carpet circling above the city, flying through spaces you never thought possible to enter. Instead of looking up at a distant dome, it was now right there, inches away. There was a familiarity to it, yet the experience was new and foreign. There was an exhilaration about it.

Standing next to the eagle, you were looking out over Concord, wind blowing, hearing the steady drone of traffic near and distant. For a brief moment you were sharing the eagle’s space, seeing his view, feeling the same wind against your face. You grabbed the rail and took it all in, a fleeting moment of confidence because you made the climb and saw the view with your own eyes.

IN THE DETAILS

For me, it never became routine. Each venture up the scaffolding was different, a witness to progress. As work continued through the summer and into the fall, I saw emerge the shine of new lumber, new windows, new paint, and new gold. The craftsmanship, attention to detail, and determination to do the best job possible guided every worker, every task, every nail driven, and every brush of paint applied. The workers all approached their job with full awareness of their task. To them, we the people entrusted the care and nurturing of a historic space and the opportunity to become part of that space’s history.

Project superintendent Bill Pritchard of DL King & Associates, Inc., general contractor for the work, kept things on schedule. Aaron Jenness, also of DL King, and his crew replaced every window and casing in the top lantern, carefully measuring, cutting, fitting, and refitting for tightness every piece of wood they used. The rotted pine was replaced with white oak. Every piece was pre-primed before being affixed and then sealed top, bottom, and side to ensure there would be no way for water to get in.

Next time you are near the State House, look up at the row of balusters that circle just below the base of the dome (also known as the spring line). There are 146 of them, and every one is new and, again, made of white oak instead of pine.

Not every part of the project was planned. Lightening protection became an unexpected challenge. In the end, a whole new system was installed. Take a close look and you will notice there are now lightning rods atop every portal window in the dome. The rod sticking up from the eagle’s head is twice as high as before. And I can attest to how tiny the space was that contractor Will Priestly disappeared into one day—just below the eagle—to install part of that system. I don’t know how he did it.

THE GOLD

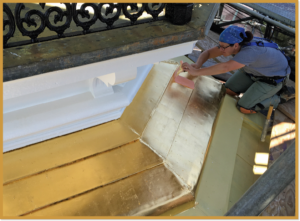

What we notice most is the new gold on the dome. EverGreene Architectural Arts is responsible for that. Step one was cleaning, which began with stripping off the old gold. Then the copper plate was scrubbed, rinsed, and scrubbed again, sometimes using brushes the size of a toothbrush. The crew cleaned every seam and crevice, bringing a bright shine back to the copper. Then it was covered with primer.

Gold leaf application is a delicate thing. Step one is laying down an adhesive material called size. It paints on clear, like a varnish, and then needs to cure overnight. The size needs to be just the right tackiness for gold leaf to adhere, and if too much time passes, it must be redone.

Gold leaf comes in three-inch-square sheets. They are made from gold that is hammered so thin it’s almost translucent. Each piece is mounted on a backing paper for easier application, similar to press type. The gilder puts the paper against the surface, gold side down, and then uses a brush or paint roller to push the gold off the paper onto the surface with the size. The paper is removed and a brush is used to permanently affix the gold in place by gently dabbing the bristles against the gold. The process is repeated over and over again.

For larger, flatter surfaces, such as the dome, the gold also came in three-inch-wide rolls, which move things along a bit faster. But for the eagle, full of feathers and indentations, the square sheets worked best.

Gold doesn’t stick to itself and there is some overlap when laying down the sheets, so little specks of gold would flutter off in the wind. Some even landed on people below as they walked through the State House Plaza. The day I recorded Jill Eide applying gold to the eagle, I discovered when I got back to my office that my camera had specks of gold covering the housing and lens.

The final step of the process is to buff the gold with a lamb’s wool cloth. This happens a day or two after the gold has been applied. It brings out the shine and polishes away any visible seams so that the gold looks like a solid surface.

We can see the gold shine. But the next time you look up, think of the care and nurturing the crew of three from EverGreene Architectural Arts put into each step of the process. They were on-site for a month and a half, working Saturdays and often on Sundays. Their attention to detail can’t be seen from the street, but they polished our dome as if it were their most prized trophy.

In November 2016 the scaffolding came down, revealing what looked to be a brand-new dome at the State House. What remains is the shine of the work done. Next time you go by the State House, give a thought to the workers who, in the summer of 2016, polished up the old girl for her bicentennial in 2019.

FINAL TALLY

• Gold used: 4.5 pounds

• White paint: 100 gallons

• Weight of scaffold: 12.5 tons

• Number of contractors

involved: 29

• Project cost: $2.4 million

A LITTLE HISTORY

Construction of the New Hampshire State House began in 1816 and was completed in 1819. As most know, it is the oldest State House in the country where the legislature still meets in its original chamber. In 1909, an addition to the building’s west side doubled the State House in size and gave it the look as we know it today.

The dome was added in 1866 and was originally covered in slate. But in 1965, Governor John King moved along a renovation project that included replacing the slate with copper covered in gold leaf.

THE EAGLE

THE EAGLE

There have been two eagles on top the State House. The first was made of wood, butternut to be precise, and put into place in 1818. It survived for 139 years until 1957, when a replacement was commissioned.

The new eagle was made of copper by Ralph Raynard of Peabody, Massachusetts. He designed it like a big weather vane, using the original eagle as his model. It is signed inside by all the people who helped Ralph in the construction.

The first layer of gold leaf was applied by Ralph’s wife Teresa while the eagle stood in the kitchen of their Peabody home. She worked on it between fixing lunch and dinner.

The new eagle was lifted into place on November 11, 1957. The next day Ralph and Teresa’s son was born, and they always equated the New Hampshire eagle with their son’s birthday.

The original wooden eagle is on display at the New Hampshire Historical Society building on Park Street.

THE PLATFORM

THE PLATFORM

One of the first things DL King & Associates of Nashua did after the state awarded them the restoration contract was calculate whether the State House roof could support the scaffolding. To everyone’s surprise, it couldn’t.

So, a special—and permanent—platform was designed that transferred the load weight of the scaffolding to the granite walls of the building. In September 2015, Turnstone Corporation of Milford installed the steel platform around the base of the dome. Concord firefighters were brought in to keep watch as the welding was done, even spending the night at the State House to guard against any possibility of fire from an errant spark. Project manager Gary Brown had a hard time sleeping, worried about getting a call that the State House was on fire.

But the installation went as planned. The steel platform was enclosed and is now a permanent part of the State House, ready to be used again for any future work that may call for scaffolding.

View Print Edition

View Print Edition

Do you have any pictures of the men putting the eagle back up after painting it. Back in the 50’s ???