Bob Averill happened upon the story of New Hampshire photographer Amos F. Clough in the depths of a Dartmouth College library in 1989. Averill was immediately drawn to Clough, who was born in Warren in 1833 and documented the landscape and people of northern New Hampshire using what was then cutting-edge photo technology. Averill was so intrigued by Clough’s story that he wanted to pull it from the darkness of history (and the library) and develop it into a book of his own.

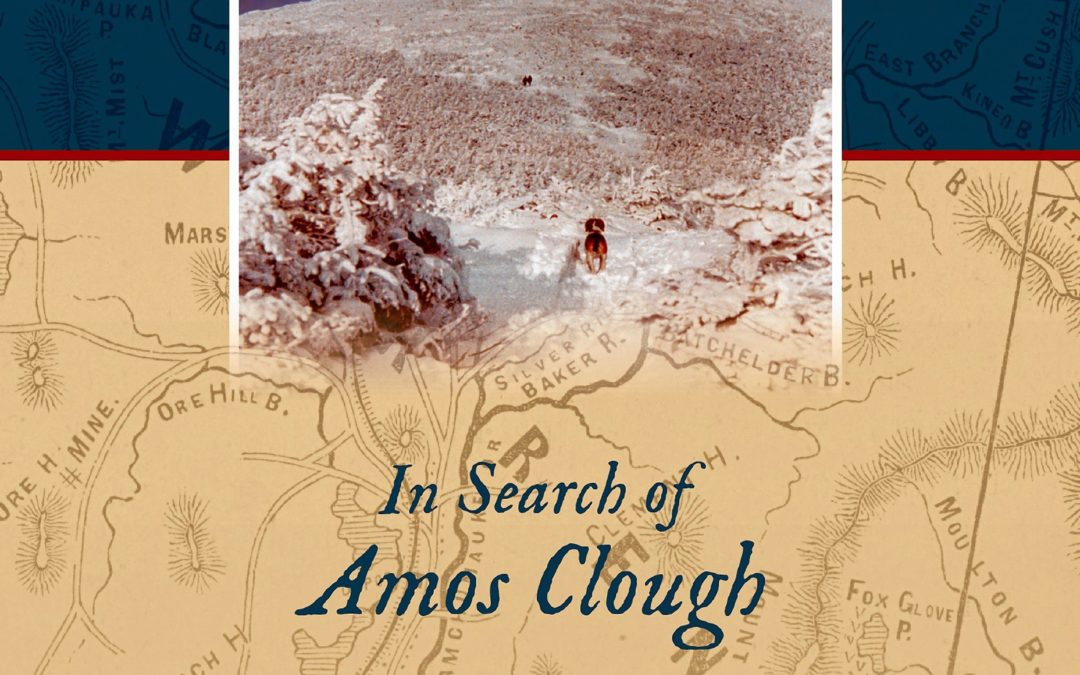

The project took 30 years, but the book, “In Search of Amos F. Clough,” is now complete. It was printed at Brayshaw Printing in Warren in late 2019 and completed by the New Hampshire Bindery in Bow in April.

One of the main reasons it took Averill so long to finish the project was a lack of source materials, and if it wasn’t for 19th-century Concord photographer Howard A. Kimball, Averill may have never finished, or even started, the Clough book.

“Clough was already the photographer on the expedition up Mount Washington in 1870, but when a man from Concord, Howard A. Kimball, expressed interest in going, Clough agreed to that and suggested that they become partners and that was a really a key to this whole thing,” Averill said. “Not only was Kimball already an established photographer, but he also came from a family in Concord that ran a large photography studio, and that made a big difference afterwards in the production of the photographs, the stereoview cards, and their availability then and now.”

Stereoview photos are central to Averill’s book. For those who don’t know, stereoviews are two nearly identical photographs taken inches apart from each other and, when viewed through lenses set approximately 2.5 inches apart (about the distance between the eyes), give the illusion of depth. Current 3D technology is based on the same basic principles as stereoview photographs.

Clough and Kimball produced thousands of stereoviews, but Averill had a tough time finding any of them when he began working on the book.

“The first 10 years or so that I was looking for them I only found one,” Averill said. “It was just in the last couple of years with more research on the internet available that I was able to find out who else had stereoviews.”

Averill, 70, also had more time to hunt for those rare stereoviews during the last two years because he retired from his medical practice. With that extra time and the convenience of the internet, Averill tracked down two private collectors with large stashes of stereoviews that he was able to buy and borrow, and he borrowed from the collections at the J. Paul Getty Museum in California, the New York Public Library and the New Hampshire Historical Society.

“I probably have the largest collection out there now,” said Averill, who lives in Shelburne Falls, Mass. “I’ve kept an eye out for more pieces by Clough and Kimball and the other New Hampshire photographers since I completed the book in December, but I haven’t found any yet.”

Most of the stereoview photographs in the book focus on the natural beauty of the White Mountains – snow-covered peaks, waterfalls, wildflowers, panoramic views – and the northern towns of Warren and Orford, where Clough had a photography studio, and their residents. But there are also a handful of stereoviews of Concord in the middle of the 19th century – a view from the statehouse cupola, a look down Main Street, a picture of the cells in the New Hampshire State Prison, a snowy churchyard and a shot of the Kimball Photographic Studio. Averill also included several stereoview photos of Shakers and the Shaker Village in Canterbury that were taken by Kimball’s older brother Willis Gaylord Clark Kimball.

“They were just too good to leave out,” Averill said of the Shaker stereoviews.

For history buffs, these old photos are fascinating to look at in just two dimensions. But for readers who want the full 3D effect, “In Search of Amos Clough” comes with a pair of stereoview lenses and some instructions on how to use them.

“It’s very peculiar, and it takes everyone a little practice, but then all of a sudden it happens,” Averill said of seeing the depth in the stereoviews. “It’s not hard, but I ended up writing a whole section at the beginning of the book on how you have to view them.”

Not only was the idea for this book kicking around in Averill’s head for 30 years, threads of the story have been weaving in and out of his life for nearly 60 years.

He first became interested in the White Mountains when he went to Camp Winona in Bridgton, Maine, and always signed up to go on the camp’s hiking trips. Those hikes were usually led by a counselor named Phil Clough, who Averill wrote about in the book: “He pronounced his name ‘Clow,’ and might have been a 10th or 11th cousin of Amos Clough, who pronounced his name ‘Kluff.’ ”

While he was an undergraduate at Dartmouth, Averill was a photographer for the school newspaper. He was also part of a group from the college that repaired and built hiking trails in the White Mountains that had enchanted Amos Clough and Howard Kimball 100 years earlier. Averill was a dermatologist for 30 years and said, “that’s kind of a visual thing, too, like photography, so I think the visual has always appealed to me.”

He also has a writer’s curiosity, which is the trait that pulled him into the depths of that Dartmouth library and helped him discover Clough’s story in the first place.

“I’m not a collector, but I like to look for stuff,” Averill said. “I like to know about things that have been lost to time.” u

View Print Edition

View Print Edition

Where may I purchase a copy of the book?

7/28/20

Thanks Tim!

You’ve done a great job telling the story of the the story of Amos Clough.

If you hear from anybody looking for this hard to find book, just let me know ar rwaverill@gmail.com. I have donated a copy of In Search of Amos Clough with a viewer to each town library in NH (about 240 books!).

Steve Smith at the Mountain Wanderer Bookstore in Lincoln is also carrying both the Amos Clough book and the 1879 Daniel Clement Moosilauke Journal.

Thanks again!

Bob Averill

Where might I purchase a copy of In Search of Amos Clough?

Article does provide an answer.

Thank you.