How the small town of Grafton became a Libertarian stronghold

The ultimate goal of the Free Towners is described in Ayn Rand’s novel Atlas Shrugged, in which a hidden valley of industrialists form Galt’s Gulch, a rogue society ruled by a pure free market. Their capitalist utopia stands in stark contrast to mainstream America, where parasitic governmental interference causes interdependent businesses — railroad lines, copper mines, and steel mills — to fail for want of basic materials, dragging those outside the valley toward a lawless dark age.

For Grafton’s Free Towners, Rand’s vision of a market-driven society was what kept them privatizing and deregulating everything they could. For seven long years, they joined thrift-minded allies in issuing vociferous challenges to every rule and tax dollar in sight; one by one, expenditures were flayed from the municipal budget, bits of services peeled away like so much flesh.

They permanently extinguished most of the town’s streetlights to save on electricity bills and discontinued long stretches of dirt road to save on highway materials and equipment. The town rejected funding for frills like community Christmas lights and Fourth of July fireworks. And though the planning board survived, Free Towners and other like-minded residents gutted its $2,000 budget, first cutting it to $500, then to a token $50.

Contrary to the libertarians’ expectations, however, real life in the Free Town seemed to be almost the reverse of Rand’s fictional vision – by 2011, while the rest of America was chugging along unperturbed, the holes in Grafton’s public services gaped stubbornly, creating a spreading malaise.

Despite several promising efforts, a robust Randian private sector failed to emerge to replace public services. A theoretical private fire department run by Bob Hull never seemed to actually stop fires. A freedom-themed farmers’ market sputtered along for a while, then faded. A proposed public-service militia never got off the ground.

Meanwhile, the constant bloodletting was turning the once-vibrant town government into a symbol of societal decay. On the town’s few miles of paved roads, untended blacktop cracks first blossomed into fissures, then bloomed into grassy potholes. After voters rejected a funding request for $40,000 to purchase asphalt and other supplies, embattled town officials warned that Grafton was in serious danger of losing the roads altogether. The town was also put on notice by the state that two small bridges were in danger of collapse, due to neglect.

Grafton’s municipal offices declined from a state of mere shabbiness to downright decrepitude. As the town clerk and a few other staffers processed paperwork and fielded citizen complaints, they stood beneath exposed electrical wires hanging from the ceiling like copper-headed mistletoe. With no money to replace the hot water system when it failed, staff were forced to wash their hands in icy water. And when the building’s envelope was breached, nature took full advantage: rainwater poured through major roof leaks and seeped into the side walls, while a biological torrent of ants and termites entered a thousand unseen cracks, crawling over walls, floors, ceilings, desks and, if they did not move frequently enough, people. Tracey Colburn, the town’s administrative assistant (seemingly one of the few people in town who did not own a firearm and who did not care for politics), resigned.

As libertarians continued to worry away services, what emerged from the fray was not an idealized culture of personal responsibility, but a ragged assortment of those ad-hoc camps in the woods, some of which began to generate complaints about seeping sewage and other unsanitary living conditions. Other indicators also seemed to be moving in the wrong direction. Recycling rates dropped from 60 percent to 40 percent. The number of annual sex offender registrations reported by police increased steadily, from eight in 2006 to twenty-two in 2010—one in sixty residents. In 2006, Chief Kenyon joined state authorities in arresting three Grafton men connected with a meth production lab in the town, and in 2011, Grafton was home to its first murder in living memory. After a man was accused of being a “freeloader” by two roommates in a temporary shared living situation, he killed them both, using a 9 millimeter handgun and a .45 to shoot one of them sixteen times. In 2013, police shot and killed another Grafton man in the wake of an armed robbery. In all, the number of police calls went up by more than two hundred per year.

In many small New England communities, the growing sense of lawlessness might have triggered an increased police presence, but Grafton’s police department was suffering the same fiscal anemia that was affecting everything else. Because of funding constraints, the department’s lone twelve-year-old cruiser was frequently in the shop for repairs; as the police chief (whose request for a salary increase was defeated by voters in 2010) noted in his annual report, the need for repairs “created a lot of down time throughout the year.”

All of these public services—roads, bridges, town offices, lighting, police mobility, and more—were sacrificed as casualties in the all-important battle to keep property taxes low.

So how low are Grafton’s taxes?

Municipal property tax rates in New Hampshire (which, remember, has no state income tax or sales tax) vary wildly. For example, the city of Claremont, a former mill town, had a 2010 rate of $11.94 per $1,000 of home value, among the highest in the state, and it spends that money on a robust offering of parks, infrastructure, economic planning, and public safety resources for its residents.

Like Claremont, Grafton is legally required by the state to provide emergency services, road plowing and upkeep, environmentally responsible waste disposal, insurance and legal services, the licensing of dogs, the maintenance of bridges, the keeping of publicly accessible town records, and other services deemed essential.

Small, rural towns tend to carry out these mandates on a shoestring budget, but some towns’ shoestrings are more frayed than others. For example, Grafton and its northern neighbor, Canaan, have similar household income stats but meet their obligations very differently. While almost all public officials in Canaan would describe themselves as fiscally conservative, Grafton has shown a savantlike talent for weaseling out of public costs.

It’s always been that way. Even in the late 1700s, when Grafton and Canaan were neighboring settlements with just a few hundred residents each, Canaan spent public dollars to feed its militia members during military training exercises, while Grafton voted against doing the same. Back then, those sorts of decisions kept Grafton’s tax rate at two pounds per thousand pounds of valuation (British currency), while Canaan residents were taxed more heavily, at two pounds, three shillings.

Both communities taxed residents with the same fiscal goal in mind of growing their populations. If a community attracts and retains people, it spreads the tax burden over more taxpayers and creates a virtuous cycle of economic growth and prosperity, but the difference between the two towns was that, where Canaan tried to attract people by emphasizing tax-funded services, Grafton emphasized lower taxes.

Inherently statist, the Canaan approach is based on the idea that elected officials are better qualified to spend taxpayer money than the taxpayers themselves. The Grafton approach, on the other hand, is individualistic: people with the freedom to spend their own money make better, more rational decisions than the government.

For two hundred years, the towns carried these differences through the quick boom and then the slow decline of the New England agricultural economy. During the boom years and up through the Civil War, both Grafton and Canaan were buoyed by the capitalistic forces that prevailed in an age of prosperity, with Grafton’s population swelling to 1,259 in 1850 and Canaan’s going a bit higher, to 1,682.

Following the American Civil War, New England’s agricultural economy migrated west, and both communities lost population. Canaan responded by investing in its future, building the sort of public infrastructure it believed would appeal to new residents.

Grafton took a different approach. In 1881, when good times created a surplus in the town treasury, they voted at a town meeting to give everyone a tax-free year. And in 1909, not long after it first declined to fund a fire department, Grafton stymied a plan to build a $150 police station, leaving a chain of police chiefs no choice but to work, conduct interviews, and store criminal records in their own homes for the next eighty-two years.

Grafton’s population in 2010 was 1,340, just a hair more than in 1850. But over that same time period Canaan’s population ballooned to 3,909, despite its higher taxes.

It was possible to think that Canaan had the better tax plan. But maybe, as the Free Towners likely believed, it was exactly the opposite: maybe Grafton’s taxes were still too high. So Grafton doubled down on its anti-tax war.

In 2001, the municipal budget included $520,000 in local tax money (a figure that doesn’t account for other revenue sources, like state grants). By 2011, the municipal budget contained just $491,000 in taxes. Factoring in inflation, the town had reduced its buying power by 25 percent, even though the population increased by 18 percent over the same time period. Not every service was being cut. Indeed, certain expense categories were expanding. Before the Free Town Project began, the town’s legal expenses were usually less than $1,000 per year — they totaled $275 in 2004. But after the Free Town Project began, a more litigious mind-set emerged in Grafton and the town’s legal bills began to mount, reaching $9,400 in 2011.

Grafton is also legally required to provide public assistance to income-qualified residents who apply. Before the beginning of the Free Town Project, providing public assistance tended to cost the town less than $10,000. But by 2010 that expense had more than quadrupled, to more than $40,000.

Grafton and Canaan have drifted so far apart that no one would guess they started as virtually identical settlements. After 150 years of community building, Canaan had an elementary school, churches, restaurants, banks, a gift shop, two bakeries, pet boarding facilities, a metalsmithing shop, meeting halls, convenience stores, farms, an arts community, a veterinary clinic, and dozens of small businesses, each of which added something to the town’s identity and sense of community.

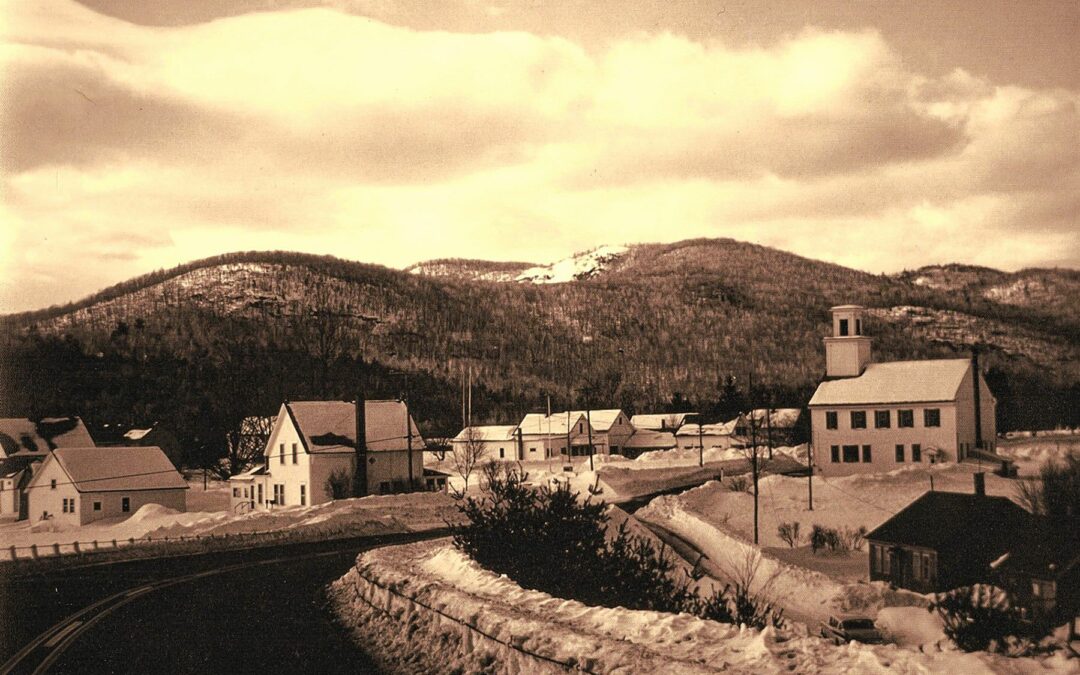

Grafton, by contrast, had a single, struggling general store, one tourist attraction in the Ruggles Mine, a suite of chronically underfunded municipal services, and a church celebrating the singular ideas of John Connell.

But Grafton had low taxes. Or, to be more accurate, taxes that were low in theory. I assumed that, after all those years of resistance, Grafton’s tax rate would be a fraction of Canaan’s, but I learned that the difference is actually quite modest. Because it has managed to maintain larger populations over the decades, Canaan can spend much more on public goods, while keeping tax rates in check. In 2010, the tax rate in Grafton was $4.49 per $1,000 of valuation, as compared to $6.20 in Canaan. That means the owner of a $150,000 home would get an annual municipal tax bill of $673.50 in Grafton, and $930 in Canaan.

In other words, Grafton taxpayers have traded away all of the advantages enjoyed by Canaan residents to keep about 70 cents a day in their pockets.

Did Canaan’s relative success really say something about taxes, or was that a coincidence? After all, high taxes can drive people out of a community, which is why many regularly vote against tax-hiking public frills like libraries, street lighting, well-maintained roads, swimming pools, tennis courts, agricultural fairs, museums, playgrounds, and gardens.

In 2019, a group of Baylor University researchers decided to check in on people who favored low taxes over these sorts of “frills.” They looked at thirty years of data on public spending on optional public services and compared them to self-reported levels of happiness. Their findings suggest that Canaan’s success is no fluke, but in fact an entirely predictable outcome: states with well-funded public services have happier residents than those that don’t.

This happiness gap held up among all sectors of society—rich and poor, well-educated and poorly educated, married and single, old and young, healthy and sick.

The researchers said that the data bore out the commonsense observation that, “when states invest in public goods . . . they often can have the effect of bringing people together in a common space and enhancing the likelihood of social interaction and engagement.” Over time, they wrote, “these subtle interactions can help to strengthen social ties among citizens and, in doing so, promote greater well-being.”

But there is one caveat. Public spending is associated with happiness, but it might not actually cause happiness, said the study authors. It’s also plausible that happy people of all income levels are simply more willing to spend tax money.

If that’s true, it would suggest that Grafton’s miserly approach to public spending didn’t necessarily cause unhappiness among its residents. Rather, the low tax rate may have been a predictable outcome for a town that had, over the years, become a haven for miserable people. u

View Print Edition

View Print Edition

Free State Project failed. Keep Grafton, Grafton!

More at Facebook group: Grafton In The Present