Not every act of heroism takes place in battle. Concord’s only 20th-century recipient of the Congressional Medal of Honor offers a case in point.

On the afternoon of Aug. 29, 1916, Charles Willey was a 27-year-old warrant officer, a machinist aboard the armored cruiser U.S.S. Memphis, anchored in Santo Domingo harbor off what is now the Dominican Republic.

Willey was playing cards with shipmates when he noticed increasing violent swells rolling in from offshore, tossing the ship at its moorings. Rushing to his quarters, Willey pulled a jumper and dungarees over his uniform, and he went below to the fire room as the order came to raise steam in the Memphis’ huge boilers and seek the safety of deep water.

Within minutes, 40-foot-high waves created by a distant hurricane washed over the Memphis.

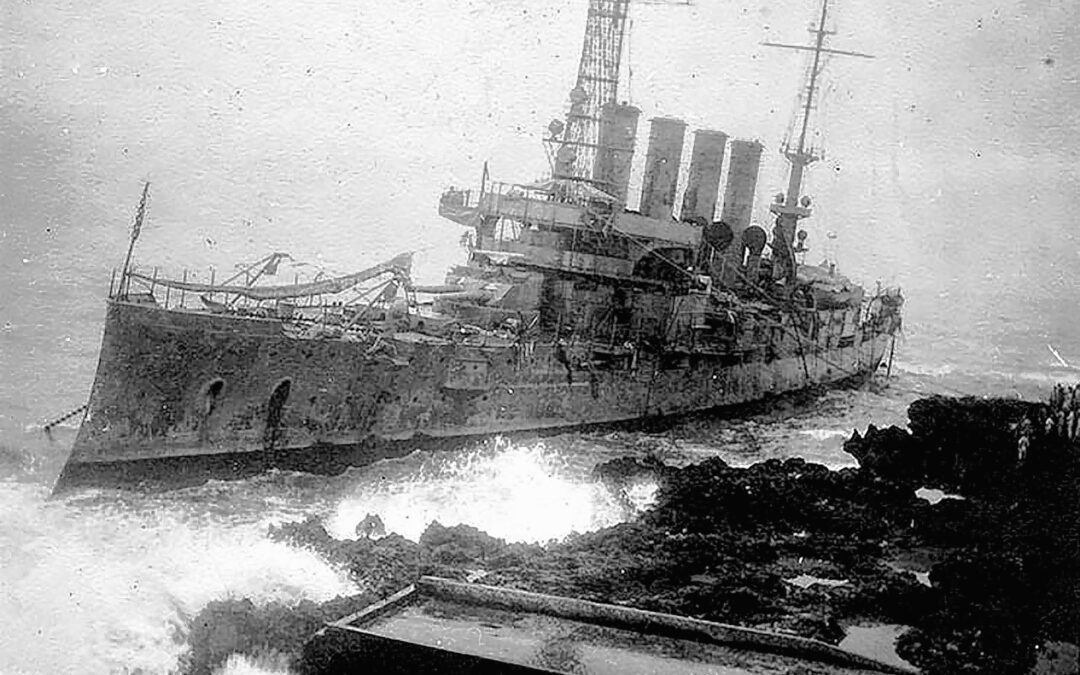

The cruiser was anchored in 55 feet of water, but its keel struck the harbor’s bottom as the Memphis plunged down the troughs between the waves. At 4:40 p.m., a wave 70 feet high thundered down upon the Memphis, completely engulfing it, snapping its anchor chains and driving it ashore.

The impact ruptured steam pipes and exploded the boilers, sending jets of scalding steam through the fire room where Willey was stationed. Tons of seawater flooded in through the open portholes. Sailors panicked and tried to flee to the upper decks. They were actually crowding into a steam-filled locker room, with the hatches to safety clamped shut.

Willey immersed himself in water on the deck of the fire room. Wearing leather gloves, and with his soaked jumper wrapped around his face, he forced his way through the screaming men and opened the hatches to free them. According to his Medal of Honor citation, he then helped dazed and scalded sailors out of the compartment, carrying them into the engine room “where there was air instead of steam to breath,” and passed out when other rescuers arrived. Out of a ship’s crew of 887 officers and men, 43 died and 204 were injured in the incident. The Memphis never sailed again.

Willey spent 18 months in Washington Naval Hospital recovering from his burns, and reluctantly retired from the Navy after World War I due to the damage to his lungs from the scalding steam. Willey moved to Penacook and worked at Hoyt Electrical Instrument Works Company for more than 45 years. His heroism was uncovered 16 years after the hurricane. He was presented with the Medal of Honor at Portsmouth Naval Shipyard on Aug. 18, 1932.

Willey died on Sept. 11, 1977, at age 88 and is buried in Maple Grove Cemetery in West Concord.

This excerpt from “Crosscurrents of Change” was written by Byron O. Champlin and is part of ‘Chapter 10: Called to the Colors – Concord residents fight and sacrifice in wartime service.’ This 400-plus page hardcover edition introduces you to the people who helped shape a city, and it takes you through tragedy and triumphs with some of the defining moments in Concord history. To purchase a copy or to learn more, visit concordhistoricalsociety.org/store.

This excerpt from “Crosscurrents of Change” was written by Byron O. Champlin and is part of ‘Chapter 10: Called to the Colors – Concord residents fight and sacrifice in wartime service.’ This 400-plus page hardcover edition introduces you to the people who helped shape a city, and it takes you through tragedy and triumphs with some of the defining moments in Concord history. To purchase a copy or to learn more, visit concordhistoricalsociety.org/store.

View Print Edition

View Print Edition