THE LIGHT, COLOR, AND ART OF SOUTH AFRICAN WOMEN AT THE CURRIER

Before Ntombephi Ntobela inspired a new tradition of South African art, she was making and selling beaded jewelry to supplement the income of her husband, a migrant sugarcane cutter working on a plantation. But the market for handmade jewelry shifted as cheaper plastic crafts became available.

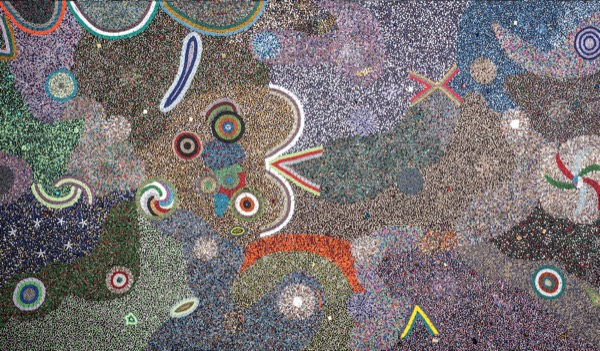

Ntombephi—along with a group of women whom she had taught the craft of beading—reacted to this shift by transitioning to a different, much larger medium. Rather than make small pieces to be worn as accessories, they turned to ndwango, a style of art where colored glass beads are applied to black fabric stretched tightly so that it can be hung on a wall like a painting. When thousands of these colored beads are delicately applied, they create a vibrant illustration.

Then in 1999—with Ntombephi as their induna, or leader—they created an artists’ collective that they named Ubuhle, which means “beauty” in the Xhosa language. Their home was a former sugar plantation in KwaZulu-Natal that they call Little Farm. Where they were once crafters of handmade jewelry, these women became creators of fine contemporary art that has garnered international praise, financial independence, and lives dedicated to their art.

UBUHLE

UBUHLE

Samantha Cataldo, curator of contemporary art at the Currier Museum of Art, says she was amazed when she got to see the work in person. A picture of one of the pieces is impressive enough, but it’s a new experience to see the details up close, she says.

“People need to see it,” Samantha says. “It is really overwhelming how beautiful it is and how intricate it is and to think about the time spent on it and how much forethought has to go into a craft like this. Every individual bead is like a pixel of color, and they have to plan it out very far in advance to create an image at the end.”

The works vary in size and imagery. The centerpiece of the exhibit is The African Crucifixion, a stunning and massive piece where the beaded fabric covers the wall from floor to ceiling. It’s made up of seven panels and through biblical images, it tells “a contemporary story about hardship and hope in South Africa,” as described by the Smithsonian.

“It’s a real technical feat but it’s also very emotional,” Samantha says. “The women in the group—some of them live together—all work together to create this craft. They make these large beaded panels, which are now travelling and collected as artwork. They also make other things like necklaces and that’s how they make their income. So, they’re using their talent and their ability in craft to gain financial independence.”

As museums have come to value the quality of their work—the first of which in the U.S. was the Smithsonian—it has validated and endorsed what these women believed their work is and what their lives are dedicated to: art. As Bev Gibson, who helped start Ubuhle with Ntombephi as cocurator in 1999, notes, “To have Dr. Jeanette Cole make the statement that the Smithsonian recognized each individual artist as international artists has elevated the status of these artists in their community, in the art world, and most importantly to themselves.”

She adds, “They were embraced by the American public as unknown artists because of the sheer beauty and integrity of their work. Further, the museums that have shown the work and the public that has visited the exhibition as well as their response—both verbal and practical through purchasing their other works—has changed these artists’ lives. And this reception among the American public of these women who have no formal art training has influenced the reception received from art collectors in Europe.”

In turn, this growing profile provides some control and autonomy as to where they exhibit, how they are represented, and how they are paid. “They no longer have to take cheap commissions because they are desperate for cash because the demand for their work is often more than they can produce in a week. They can therefore negotiate their own terms,” says Bev.

This financial freedom described by Samantha and Bev is a significant part of the larger meaning behind the exhibit Ubuhle Women: Beadwork and the Art of Independence. Many in South Africa were living in poverty when the group formed in 1999, and Little Farm became a retreat for creative women seeking artistic opportunity. They continued selling jewelry to remain financially independent while raising their families and working on ndwangos, one panel of which takes more than 10 months to make.

This financial freedom described by Samantha and Bev is a significant part of the larger meaning behind the exhibit Ubuhle Women: Beadwork and the Art of Independence. Many in South Africa were living in poverty when the group formed in 1999, and Little Farm became a retreat for creative women seeking artistic opportunity. They continued selling jewelry to remain financially independent while raising their families and working on ndwangos, one panel of which takes more than 10 months to make.

The result is an array of beaded work done in a variety of styles unique to each artist’s approach and inspiration. These different voices are captured in each piece, and collectively they create an exhibit that is new and unique to the world of contemporary art.

“Some people work in more colors, some people like certain patterns, some women use similar design elements repeated in their works,” Samantha says. “It’s kind of a signature element to them. It’s beautiful to see that sort of evolution.”

BRINGING UBUHLE TO NEW HAMPSHIRE

Traveling art exhibits crisscross the nation, introducing communities to new and intriguing works that explore different corners of creativity from around the world. Before coming to New Hampshire, Ubuhle first opened in Washington, D.C., in late 2013. The Currier Museum—celebrating its centennial this year—will be the first in the Northeast to host the exhibit, which made its last stop at the Chrysler Museum of Art in Norfolk, Virginia, in February.

Planning for a traveling exhibit is usually done years in advance. According to Samantha, the Ubuhle exhibit came to their attention about two years ago. The museum’s curators came together and with Director Alan Chong decided to try and bring the exhibit to Manchester. Asked what attracted them to this collection, Samantha says that they’d never before seen work quite like it.

“It is a completely new artform for the most part,” she explains. “The art these women are making is unique to them. It’s taking a traditional craft that certainly other people practice in different forms, but they’ve turned it into this incredible artwork. The craft of beading is normally applied to things like clothing, but they use it to create this brilliantly alive artwork. It’s on the wall, it’s framed, it looks almost like a painting when you approach it but then you realize it’s made up of thousands and thousands of tiny, tiny glass beads. So, it’s quite labor-intensive, but they’re abstract and some are representational, or they have figures in them, and they can tell stories.”

The Currier Museum’s own collection is primarily European and American art. It has a strong collection of craftworks and contemporary art by African-American artists, but little from artists working in Africa. “This kind of traditional beadwork is something a lot of museums don’t really have,” Samantha notes. “It’s very special and unique. We thought it was a great opportunity to show something new, and then also have some connections to other collections we have with craftwork.”

STORIES TOLD BEAD BY BEAD

When Ubuhle Women: Beadwork and the Art of Independence opened at the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum in Washington, D.C., in December 2013, the museum’s director, Camille Giraud Akeju, wrote that she was “amazed by the intricacy of the beading” and the “majesty” of the large-scale works. But what moved Camille the most, and ultimately led her to bring the exhibit to the United States, were the artists’ stories and how they were told through the work.

When Ubuhle Women: Beadwork and the Art of Independence opened at the Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum in Washington, D.C., in December 2013, the museum’s director, Camille Giraud Akeju, wrote that she was “amazed by the intricacy of the beading” and the “majesty” of the large-scale works. But what moved Camille the most, and ultimately led her to bring the exhibit to the United States, were the artists’ stories and how they were told through the work.

“What seemed truly remarkable was the story behind the Ubuhle artists and their efforts using their own skills to build a self-supporting community of artists to empower local women and to provide a better future for children,” Camille wrote in a statement at the exhibit’s opening.

Ntombephi—the induna of the Ubuhle group—learned to bead from her grandmother, which inspired her use of patterns and vibrant colors. Ntombephi was a master at beading when she started Ubuhle with cocurator Bev Gibson. The group was the result of their shared vision to combine skills and create jobs for women in rural South Africa. She believes her title, induna, carries with it a responsibility to the future of the group and its work. And she hopes to firmly establish the Ubuhle guild so children may learn to bead.

Ntombephi’s piece My Sea, My Sisters, My Tears shows her masterful command of color as thousands of different shades of blue beads come together to form a radiant image of water. The piece symbolizes human connection in its most basic form. As Ntombephi describes it, “Water is the connection between all that lives. We are all related by water and water is the source of life.”

Zondlile Zondo, an Ubuhle artist who joined the group in 2008, uses a broad palette of colors in her beadwork. In My Mother’s Peach Tree, a piece from 2012, Zondlile employs explosive reds and bold patterns to show us a peach tree that stands out as a memory from her childhood. Her mother loved the tree, and “When planning this ndwango, I had a sudden memory of that tree where my mother used to sit when we were extremely poor. We didn’t even have our own home and my mother was striving so that things would be okay for us, but we had this peach tree and when it bloomed it was blazing, blazingly beautiful.”

The largest piece in the exhibit, The African Crucifixion, was originally created for the Anglican Cathedral in the South African city of Pietermaritzburg to hang in a large space behind the pulpit. The piece was created by seven Ubuhle artists, led by Ntombephi, and took nearly a year to complete.

The artists use three trees to tell a story of hardship and hope in South Africa. The Tree of Destruction symbolizes the suffering of Jesus, the Tree of Sacrifice in the center represents the crucifixion itself, and the Tree of Hope to the right represents Jesus’s resurrection.

While the piece illustrates a biblical story, it is “seen through the eyes of a community of women who are dealing with the key issues of 21st century life in rural South Africa: health, food, water, jobs, and security,” notes the Smithsonian.

LOOKING FORWARD

Ubuhle is continuing on their artistic mission, to be sure. According to Bev this includes working hard on two private commissions as well as working with galleries in Paris and Geneva, Switzerland.

“We need to make sure that we have the capacity to create art for all these institutions and have work available in America,” Bev says. “Our hope is that the exhibition will continue to travel and that curators from the U.S. west coast will visit the exhibition and host it in their museums.”

For more information on the exhibit and other features coming to the Currier Museum of Art this spring and summer, visit currier.org. Ubuhle Women: Beadwork and the Art of Independence runs through June 10.

View Print Edition

View Print Edition